Page 12 - History 2020

P. 12

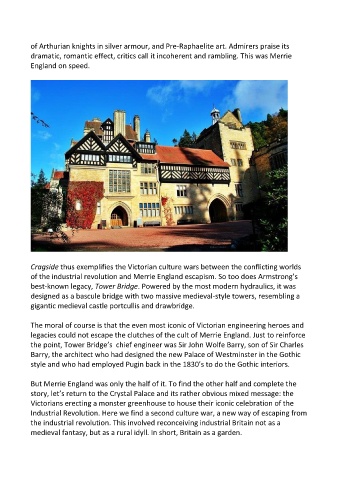

of Arthurian knights in silver armour, and Pre-Raphaelite art. Admirers praise its

dramatic, romantic effect, critics call it incoherent and rambling. This was Merrie

England on speed.

Cragside thus exemplifies the Victorian culture wars between the conflicting worlds

of the industrial revolution and Merrie England escapism. So too does Armstrong’s

best-known legacy, Tower Bridge. Powered by the most modern hydraulics, it was

designed as a bascule bridge with two massive medieval-style towers, resembling a

gigantic medieval castle portcullis and drawbridge.

The moral of course is that the even most iconic of Victorian engineering heroes and

legacies could not escape the clutches of the cult of Merrie England. Just to reinforce

the point, Tower Bridge’s chief engineer was Sir John Wolfe Barry, son of Sir Charles

Barry, the architect who had designed the new Palace of Westminster in the Gothic

style and who had employed Pugin back in the 1830’s to do the Gothic interiors.

But Merrie England was only the half of it. To find the other half and complete the

story, let’s return to the Crystal Palace and its rather obvious mixed message: the

Victorians erecting a monster greenhouse to house their iconic celebration of the

Industrial Revolution. Here we find a second culture war, a new way of escaping from

the industrial revolution. This involved reconceiving industrial Britain not as a

medieval fantasy, but as a rural idyll. In short, Britain as a garden.